Muhammad Ali knew minorities, poor will always be cogs in American war machine

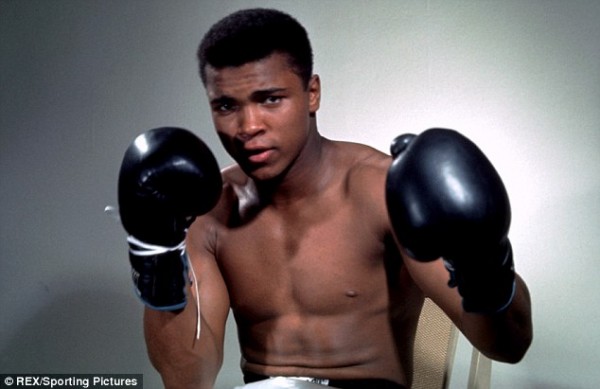

Muhammad Ali

My father, a retired U.S. Air Force colonel and judge advocate general who died a little over two years ago, was no fan of Muhammad Ali, the boxing great, poetic civil-rights activist, pacifist and convicted draft dodger who died on Friday at age 74.

My dad stubbornly refused to call Ali by anything but his given name, Cassius Clay, and outright rejected the heavyweight champion and Olympic gold medalist’s conversion to Islam and conscientious objection to the Vietnam War.

To my father, whom I respect, love and admire immensely – and to many American military men of that generation – Ali was a traitor, and they refused to concede anything to a man who refused to be inducted into the military draft and fight for his country in Southeast Asia.

“I ain’t got no quarrel with those Vietcong …No Vietcong ever called me nigger.” Ali famously said, referring to the institutional racism rampant in the United States at the time, which continues to thrive in less overt ways to this day.

“My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America,” Ali continued. “And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape and kill my mother and father … Shoot them for what? How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.”

Ali was arrested in April of 1967, convicted of draft evasion, stripped of his heavyweight title and sentenced to five years in prison, which he avoided while appealing his conviction that was ultimately overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court.

One must remember that the Vietnam War was one of the most divisive military actions in the history of the United States – sparking massive protests — in many ways because it was a Cold War proxy action conducted to combat the spread of Communism in a former French colony.

But dubious motivations aside, the Vietnam War was wildly unpopular on the home front mainly because of a draft that forcibly inducted a disproportionate number of poor, young, rural and ethnic minority Americans and sent them into a quagmire of combat with no real mandate for overwhelming victory. If you had money and connections, it was a lot easier to avoid the draft.

Some saw the Communist Vietcong as a scourge that, if not stamped out in Vietnam, would spread to the shores of America. Many see the same threat today in the form of radical Islam flourishing in parts of the Middle East, Africa and Asia, and the United States has been engaged in two military actions in Iraq and Afghanistan that have lasted far longer than the Vietnam War.

So why no massive protests roiling on the mall in the Washington, D.C.? Why no polarizing national debate over two wars that have cost this national trillions of dollars in blood and capital but netted no tangible results in terms of stabilizing the region and removing the radical Islamist threat?

I would argue it’s because there is no longer a compulsory military draft Instead, we’ve transitioned to a full-time, standing, professional military system that continues to lean disproportionately on poor, rural, inner-city and ethnic minority Americans who need the work – even if it may require the ultimate sacrifice.

My father agreed with me on that front. He wanted the draft reinstated, feeling it would then make it much harder for the United States to jump headlong into military interventions like the one in Libya that ousted Muammar Gaddafi.

We saw eye to eye in opposing that intervention in 2011, ostensibly to prevent the dictator from slaughtering his people, and an action backed heavily by then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. Ali’s death gives us an opportunity to reexamine how the U.S. military system is structured and utilized, and how its potential reform should shape the current presidential race.

While I think a female perspective would be a good thing in the White House – both from a conflict-resolution standpoint and on the critical income-inequality front – I have a huge problem with Clinton’s hawkish eagerness to plunge the nation into bloody, economically devastating armed conflicts around the globe.

As a New York senator she voted in favor of the invasion of Iraq in 2003, and that decision and the failure to properly manage the war’s aftermath continue to haunt us to this day. Clinton has repeatedly admitted she “got it wrong” on Iraq, blaming the Bush administration for its handling of the campaign to get rid of Saddam Hussein, but to me that hindsight doesn’t excuse her lack of foresight.

Still, I prefer her self-reflection to the outright lies of Donald Trump, who during his say-anything bid for the GOP nomination has repeatedly claimed he was always against the Iraq War. “I never supported the Iraq War” has been Trump’s consistent refrain on the campaign trail.

The problem is, radio shock jock Howard Stern in 2002 asked Trump, “Are you for invading Iraq?” and Trump answered, “Yeah, I guess so. I wish the first time it was done correctly.” He also has lied about his original support of the Libya intervention, saying he was against it all along.

So do we want someone in the White House who has bad judgment about matters as critical as armed conflict but is willing to hopefully learn from her mistakes, or do we want someone with bad judgment who is willing to full-on lie to our collective faces about that lack of judgment?

And if we are to commit hundreds of thousands of ground troops to another conflict aimed at regime change that merely creates power vacuums for extremist groups, who will pay the highest price for such a decision? Trump espouses isolationist views that seem misguided at best, but he’s proven he’ll say anything to get the GOP nod, meaning he may reverse course if elected.

Clinton wants more special forces in Syria to combat Isis and try to correct the mistakes of Iraq, although for now she’s ruling out mass deployments to either defeat Isis or try to oust President Bashir al-Assad. Still, small deployments of advisors and special ops often lead to mass deployments (see the Vietnam War), and even though there is no compulsory draft these days, we all know where most of those troops will come from – the lower tiers of our society.

While Trump continues his racist rants against Mexican-American judges and doubles down on his promise to build a wall on the Mexican border and ban Muslims from entering the United States, he seems oblivious to the fact that some of the earliest casualties of the 2003 Iraq invasion were undocumented immigrants from Mexico and throughout Latin America.

In fact, there were 38,000 undocumented workers in our armed forces at the time of the invasion in 2003. It’s now seen as a faster path to citizenship, so we are continuing to rely on the poor, disenfranchised and desperate to not only do the hard labor most Americans eschew, but also to fight misguided wars that only seem to exacerbate instability in the Middle East and by extension Europe, where most war refugees are fleeing.

Trump’s demonizing of Mexican-Americans and Latin American immigrants and his promise to build a wall and make Mexico pay for it is apparently engaging that voting sector and driving voter registration heading into the California primary.

Contrast Trump’s agenda with Hillary Clinton’s calls for a more lenient deportation policy than the Obama administration’s and a push for comprehensive immigration reform in her first 100 days in office and it’s easy to see the dramatic differences between the two candidates on this issue.

Immigration is not only an economic and national-security issue, but perhaps the most pressing humanitarian crisis of our time – one that I doubt Muhammad Ali would have shied away from.

Latest posts by David O. Williams (see all)

- During National Small Business Month, Target, DreamSpring put funding bullseye on underrepresented communities in Denver area - May 29, 2025

- Colorado senator urges Supreme Court to hold Trump administration in contempt on deportations - April 19, 2025

- Conductor who brought back Colorado ski train wants to use rail to save state’s highways for skiing - March 20, 2025

You must be logged in to post a comment Login